A new era for Heat Planning in the Netherlands

“The Netherlands needs to shift its thinking on the potential of district heating.”

In the Netherlands, district heating networks are usually planned and developed neighbourhood by neighbourhood. This approach has made many projects unfeasible. In Denmark, they do this differently. The Danish method argues that designing a network for a single neighbourhood is far from ideal. Instead, planning should be done at the city or town level, keeping the long-term vision (2050) in mind, following the principle: "Plan big, start small."

The current Dutch approach and its weaknesses

In the Dutch framework for heat transition, municipalities are given the responsibility and control over the planning of the alternatives for natural gas. The national government has provided several tools for planning, such as the Startanalyse (PBL). Municipalities have been given the assignment to create a Heat Programme or Warmteprogramma (NPLW). When it comes to legislation, there is the WCW (Collective Heat Supply Act) and the WGIW (Municipal Heat Instruments Act). The entire framework promotes a neighbourhood focussed strategy that relies on a single sustainable heat source.

A little background: The Netherlands started splitting up the country into postal code areas in the 1950’s. These were developed to guarantee efficient and precise mail delivery. This divide in neighbourhoods has also been used since then to collect data, create policy and to develop spatial planning because it was a clear mapping of the country.

We’ve seen that these regulations and accompanying tools, which use the mapping of our areas into postal code neighbourhoods, cause two problems. First, the heating network is considered an island and is not part of a larger development or designed for scaling up. This doesn’t fit the ‘Plan big, start small’-approach. Second, the tools provided do not offer enough insight into which areas have the most potential for developing a district heating network. Data is mostly collected and presented on a neighbourhood level, including buildings with less energy use, which causes a dilution of the presented heat demand. We argue that focusing on heat density is more effective and allows for a better result. It is therefore necessary to present a new approach and advocate for steering away from the current Dutch approach towards a new era.

So what’s different in the Danish approach?

Denmark has been doing sustainability planning for several decades. Their approach stands out because the starting point is an entire region or city, offering advantages in scaling and energy source strategy. The planning is big, while the development is compartmentalised into specific areas with a threshold of heat demands and availability of affordable energy sources. This gives the flexibility to move along with developments and respond to market shifts or new heat sources. These individual projects are respectively also designed with robustness. Most of them start off with one source but, over time, they add sources or assets such as accumulation tanks, seasonal storage and e-boilers to create the flexibility to respond to price variances on the electricity market. This, in turn, creates price stability on the consumer side. The regulatory framework in Denmark helps by forcing district heating companies to provide heat at the lowest available price, but it doesn’t regulate the number of sources added to a district heating system. This last element is something that has gradually evolved in the Danish heat market, from the principle of planning big and starting small, although we can also imagine that some competitiveness between district heating companies has played a role in this development.

Fryslân as a starting point for a new perspective

In the province of Fryslân, people have a tendency to take a different approach. The region has an own language, spends time and efforts to promote cultural heritage, and many Frisians are proud of their province. While that seems unconnected to district heating, it plays a big role in the discovery of weaknesses in the current Dutch framework. The region consists of 11 cities, and over 400 villages of very different sizes. It is not much of an urban area, as most of it is rural which is also the case for parts of other provinces. Most of the regulatory framework for district heating in the Netherlands was developed from an urban perspective. This makes sense because district heating was previously not considered viable, mostly because of extremely low natural gas prices.

New mapping tool for Fryslân and the Netherlands:

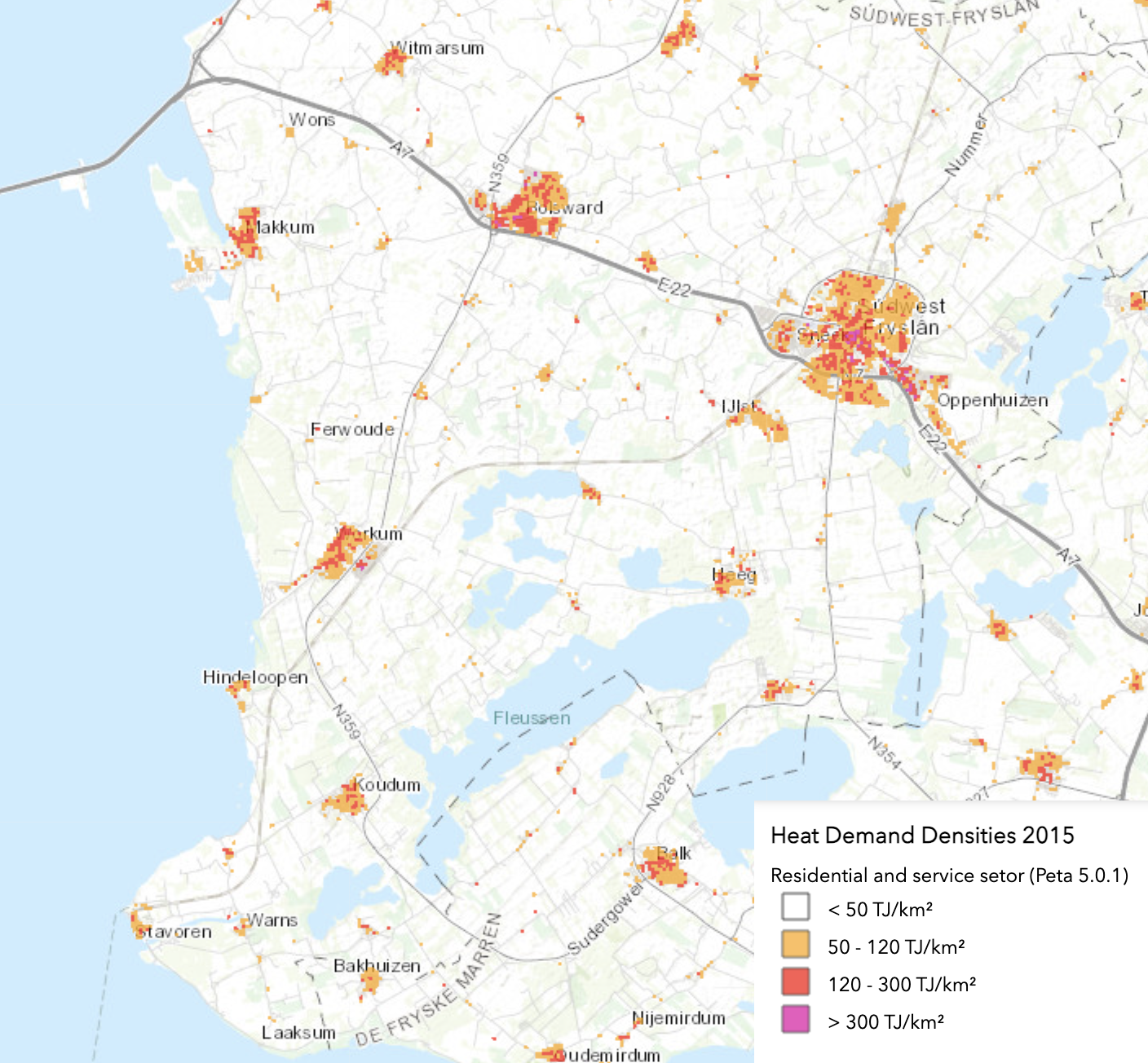

After the discovery of how unsuitable the Startanalyse-tool was for Fryslân, we were determined to create our own mapping tool. The inspiration for this tool was the PETA 5.2 map (See below), which was developed in a European research project. The PETA map uses data on heat demand provided by electricity distribution system operators (DSOs) and other open data sources to generate an overview of areas that meet a certain heat demand threshold. This information is then displayed on the map, as shown below (Figure 1).

Figure 1: PETA 5.2: District heating potential from 50-120 TJ or higher of Súdwest-Fryslân.

In the Frisian mapping tool, we use the same principle but with greater detail. Therefore, we thought that we would need data from each individual building which posed some privacy issues. Instead, we start with data on neighbourhood-level and add all data we have from the municipalities and the province when it comes to remodelling, usage space, isolation measures and so on. This is then distributed over the individual buildings in order to get a good estimation of the building's energy usage. This is than aggregated to a less detailed scale where it is presented as heat density. The mapping tool highlights the areas where it makes sense to develop district heating. Initial results show a significant difference in the projected areas for district heating in the municipality of Súdwest-Fryslân: the Startanalyse estimates 5% are suitable, whereas our model suggests 70%.

Next steps to implementation in the Dutch context

Pre-feasibility study

After a location is chosen using the heat potential map, a pre-feasibility study* is needed for the cities/towns with the highest district heating potential. The pre-feasibility study is performed at the scale of the entire built area. To carry out this study, it is essential to map out both heat demand and available (residual) heat sources and consider the layout of the pipe network at the final stage of the project (2050).

*A pre-feasibilty study is exactly as described. A fairly rough, but still based on fundamental data, scan of the options – often done by an experienced consultant. It costs far less than a full feasibility study but gives a picture of where district heating is clearly an option, where it is clearly not and where it needs a bit more investigation (or can simply wait).

How to work the source strategy

As outlined in the Danish approach, after planning for a larger area, it is time to select smaller areas for development. Heat demand is matched with available heat sources, taking into account energy prices in the Netherlands. This approach identifies the optimal energy mix for the local area, forming the initial heat supply strategy. It is necessary to have a good picture of all the available residual heat sources, from factories or wastewater treatment plants for instance. The different heat sources start small in the beginning of the project and develop as the district heating network grows. Following the Danish strategy, there is time to grow so it is not necessary to make the energy sources 100% sustainable right from the start. The sustainability percentage fluctuates throughout the project. For example, a heat pump may provide 50% of the heat during the first phase of the project but, as more houses are connected in the second phase, this percentage may drop to around 30%. Once a sufficient number of homes are connected, it becomes possible to add a second heat pump, increasing the percentage back to 60%. The goal remains to achieve a fully 100% sustainable energy mix by 2050.

Buffering is a no-brainer

One core principle is that energy sources should always be able to respond to the energy market, ensuring that consumers receive heat at the lowest possible rate. To achieve this, heat must be buffered when prices are low so it can be used when needed. This buffering can take place over different timeframes, ranging from day-night cycles to several days or entire seasons. For example, heat can be stored during the day when the sun is shining and released in the evening when demand is highest. Similarly, energy can be stored over multiple days when there is an abundance of wind power and used later when needed.

Structuring the heat sources

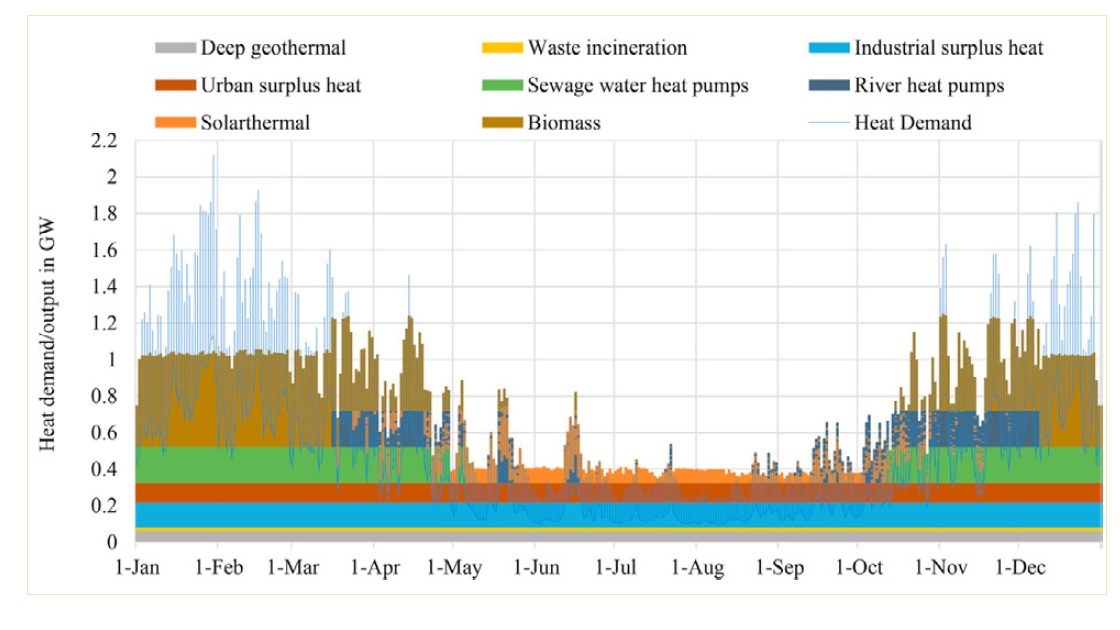

A logical configuration of heat sources is to use residual heat year-round, heat pumps and electric boilers when the electricity price is low, and gas or biomass when it is very cold outside. The energy mix of the heat sources is structured as follows: base load, medium load, peak load, and reserve capacity. Figure 2 illustrates the different heat source in Hamburg, Germany.

Figure 2: District heating Hamburg’s heat source strategy.

Location of the generation site

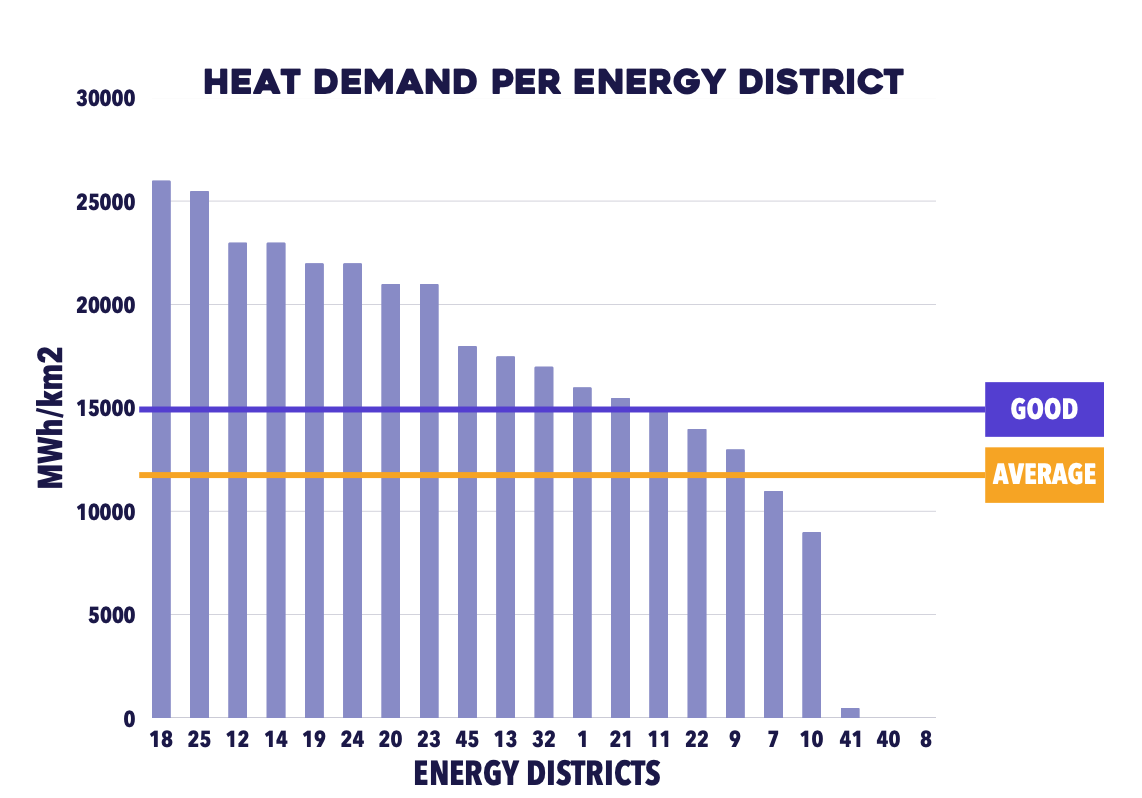

Based on this data, a suitable location for the generation site can be determined, and a preliminary network design is mapped for the entire urban area. The result of this pre-feasibility study is a tariff for the entire area, calculated using capital expenditure and operating expenses over a 30-year (or longer) period. Additionally, the analysis highlights which neighbourhoods improve the overall tariff and which would negatively impact it (Figure 3). This method enables the implementation of district heating even in neighbourhoods that would otherwise be too expensive under a traditional approach..

Figure 3: Energy districts in a city

Bolsward: case example

Bolsward is a city with 4,400 households, including a local industrial sector that produces residual heat. As an old Hanseatic city with 1,600 buildings, Bolsward features a historic centre with high heat demand and newer residential developments on the outskirts. Given the presence of local industry and the high concentration of heat demand in the city centre, Bolsward is a logical location for a district heating network, a conclusion confirmed by the pre-feasibility study.

Compared to the Dutch approach, the Danish pre-feasibility study paints a very different picture. When Bolsward is considered as an entire city and not singular neighbourhoods, Bolsward is feasible. The heat demand of the city (above 15kWh/m2) is 48.900MWh/year. The residual heat sources are Hochwald, a milk factory and the wastewater treatment plant. Furthermore, the combination of sources considered is a water source heat pump (1MW), electric boiler (5MW), gas boiler (5MW) and a thermal energy storage.

Earlier studies for a district heating network in Bolsward showed that residual heat of Hochwald alone with a connection to the neighbourhood Bolsward North wasn't feasible. The gap in the business case was €8.700 per household. This is mainly because the capital expenditure to make the residual heat available was too expensive given the limited amount of connections to spread this cost. As a result, the estimated capital expenditure was too high.

Conclusion

Previous neighbourhood-based projects have proven difficult to implement as they lack the integrity, scaling and vision to be successful. The narrative and methodology presented above demonstrates that a municipal wide plan, with a city-wide approach, significantly increases the feasibility and affordability of district heating. Combined with an optimized energy mix, the business cases not only become stronger but also create opportunities for district heating in neighbourhoods which would otherwise be unfeasible. This creates a massive shift in the strategy for the heat transition in Fryslân, but also in other more rural areas in the Netherlands. We strongly advocate for the adoption of this new methodology, focusing on making district heating affordable, while also considering its impact on grid congestion, community cohesion, and the independence of local energy systems.