A new approach to district heating in rural areas

District heating in the Netherlands started several years ago with pilot projects like Warm Heeg in the ‘Programma Aardgasvrije Wijken’ (Program Natural Gas-Free Districts). The goal was to help local initiatives and municipalities learn how to create alternative heating options for homes so that they are no longer dependent on natural gas by 2050. In recent years, Sudwest-Fryslân launched more pilot projects with the goal of gaining knowledge and experience in insulation, heating technologies, and different housing types. We took on this challenge with the available expertise and support from the regional and national government.

In the Netherlands, district heating is approached on a project-based approach, often at the neighborhood level using district codes, supported by various national policy documents. However, these boundaries were never designed to optimize the distribution of heat demand. Key factors such as housing type, heat density, and other relevant aspects are often not considered. The boundaries of districts and neighborhoods primarily serve as a visual tool for presenting statistical data. As a result, district heating projects were often developed to make one specific neighborhood gas-free.

Since then, we as a municipality have learned a great deal. Initially, we focused on pilot projects where we identified coupling-opportunities as one of the key factors for successfully implementing a district heating network. These pilots were used to understand the complexities of transitioning homes away from natural gas. This process raised many questions, such as what heat sources are available, and do we have them in our municipality? Which construction companies have experience with district heating? Who are the key stakeholders? Many of these questions have been gradually answered through our pilot projects, particularly in Warm Heeg and The Island (Het Eiland) and the Danish lessons from the Projects Frontrunner City II and Confidence.

The need for a new approach

District heating is not common in rural areas of the Netherlands, and trust in the system is low. This is due to the limited experience with collective heating solutions outside urban areas and uncertainty about affordability and reliability. However, sustainable and collective heating solutions can play a key role in the energy transition, even in rural regions.

Our approach did not emerge overnight. It has been built through continuous learning from our pilot projects, developing a well-structured methodology, and the question about which role we should take as a municipality. This has involved exploring the concept of a municipal heating company. With the knowledge we have now, our approach would look different if we were to start again today. At the core of our approach is the concept “Plan big, start small.” This means we first plan for the entire municipality, then focus on the city or town where we begin. Finally, we roll out district heating, step by step, in a phased approach, gradually covering the whole area.

In our projects, we now look for four necessary factors which we know heavily influence the feasibility of a project:

High heat demand density

Heat demand density measures the amount of heat required per hectare. This metric helps assess the density of heat demand within a neighborhood. Simply put, how much heat is used in a given area. This heat demand is essential for the feasibility of a district heating network. After all, for a district heating system to be economically viable, there must be sufficient demand to generate enough revenue. It is important to note that this does not mean only city centers are of interest. Most residential areas where people live close together are often viable, especially in the context of the Netherlands where urban areas are quite dense.

Nearby (residual) heat sources

Affordable (residual) heat is an important factor for a viable business case. Industrial processes often generate heat as a byproduct which typically needs to be cooled before being discharged into rivers or canals. This represents a waste of usable energy. This excess heat can be captured and repurposed to warm homes. A good example is a wastewater treatment plant. These plants are essential for clean water and, as a result, the continuity of these plants is assured. The heat of these plants is now often wasted, while it can be enough to provide entire cities with heat. In addition, centralizing heat sources like heat pumps is much more efficient than having individual heat pumps in each home. The scale of these sources matters. By centralizing them and producing heat on an industrial scale, efficiency is significantly increased.

Large consumers

Incorporating businesses can be highly beneficial both for achieving corporate climate goals in Súdwest-Fryslân and for ensuring a solid business case for the district heating company. Businesses, like a hospital or swimming pool, provide a stable heat demand, creating a reliable revenue stream which helps keep heating costs lower for residents.

The Transitievisie Warmte (Heat Transition Vision) for Sudwest-Fryslân, based on the national strategy, initially focused primarily on making homes gas-free. However, this turned out to be too narrow an approach.

Not immediately 100% sustainable

The ultimate goal of the district heating transition is to eliminate natural gas use by 2050. Striving for full sustainability from the outset can lead to costly infrastructure, such as district heating networks equipped with heat pumps capable of meeting peak demand even on the coldest days of the year. However, these peak demand periods occur only a few times a year.

This approach is unnecessarily extreme, whereas a more cost-effective alternative exists. A heat pump can be used that, in almost all cases, has sufficient capacity to provide the required heat. For exceptionally cold days, a backup gas boiler can be kept on hand. These gas boilers also serve as a crucial back-up system, ensuring continuous heat supply in case of system failures. In practice, the sustainability percentage changes over time. At first, a heat pump might provide 50% of the heat, but as more houses connect, this could drop to 30%. Later, adding a second heat pump can raise it to 60%.

Fresh start: how do you start as a municipality?

Within the project, we have aimed to create a new blueprint for other municipalities in their goal to successfully roll-out district heating. In the following part, we will outline these steps, each time highlighting experiences and actions of the municipality of Súdwest-Fryslân.

Step 1: Defining the municipality’s role

What role do you take as a municipality? Do you establish your own energy company, or do you collaborate with one or more partners? Think of other municipalities, grid operators, or private enterprises. If the municipality takes on a role in the district heating company, it is important to consider control and governance in advance. This is a crucial first step.

Súdwest-Fryslân

In Súdwest-Fryslân, we have recently created our own municipal heating company. Through this company, we aim to provide affordable and sustainable heating. This limited company will be fully owned by the municipality. We have placed the municipality’s role firmly in the driver seat. We are currently following this approach and expanding it as we progress. Part of this process involves sharing our new approach with stakeholders and receiving their input, allowing us to refine and improve it.

Step 2: Masterplan and laying the foundations

The municipality may decide not to take on a central role in the heat transition. If this happens, it will probably encounter bottom-up initiatives (initiatives from residents), which will take the lead. When an initiative emerges enthusiastically in a village or neighborhood, the municipality may choose to support these initiatives which can create certain expectations. The question is whether this project aligns with the necessary central vision to keep the transition affordable and whether it fits within the optimal phased sequence of projects.

This question can only be answered if there is insight into the ideal ranking of projects within the "big plan." That is why it is crucial to develop a Masterplan for the entire municipality. This plan should identify which villages, towns, and neighborhoods are the most promising for a district heating network and which areas are less suitable for such a solution. The key in Denmark is that multiple neighborhoods. or a combination of them, form energy districts. These zones are selected because they benefit from district heating, allowing areas to be grouped together within a single phase.

The ranking of projects is determined by factors such as the highest heat demand density per square meter in the area, combined with the availability and location of (residual) heat sources and the presence of large consumers or housing corporations that can ensure a stable demand for heat. When these conditions are met, projects can be ranked accordingly. If local support exists for certain projects within this ranking, those projects naturally take priority.

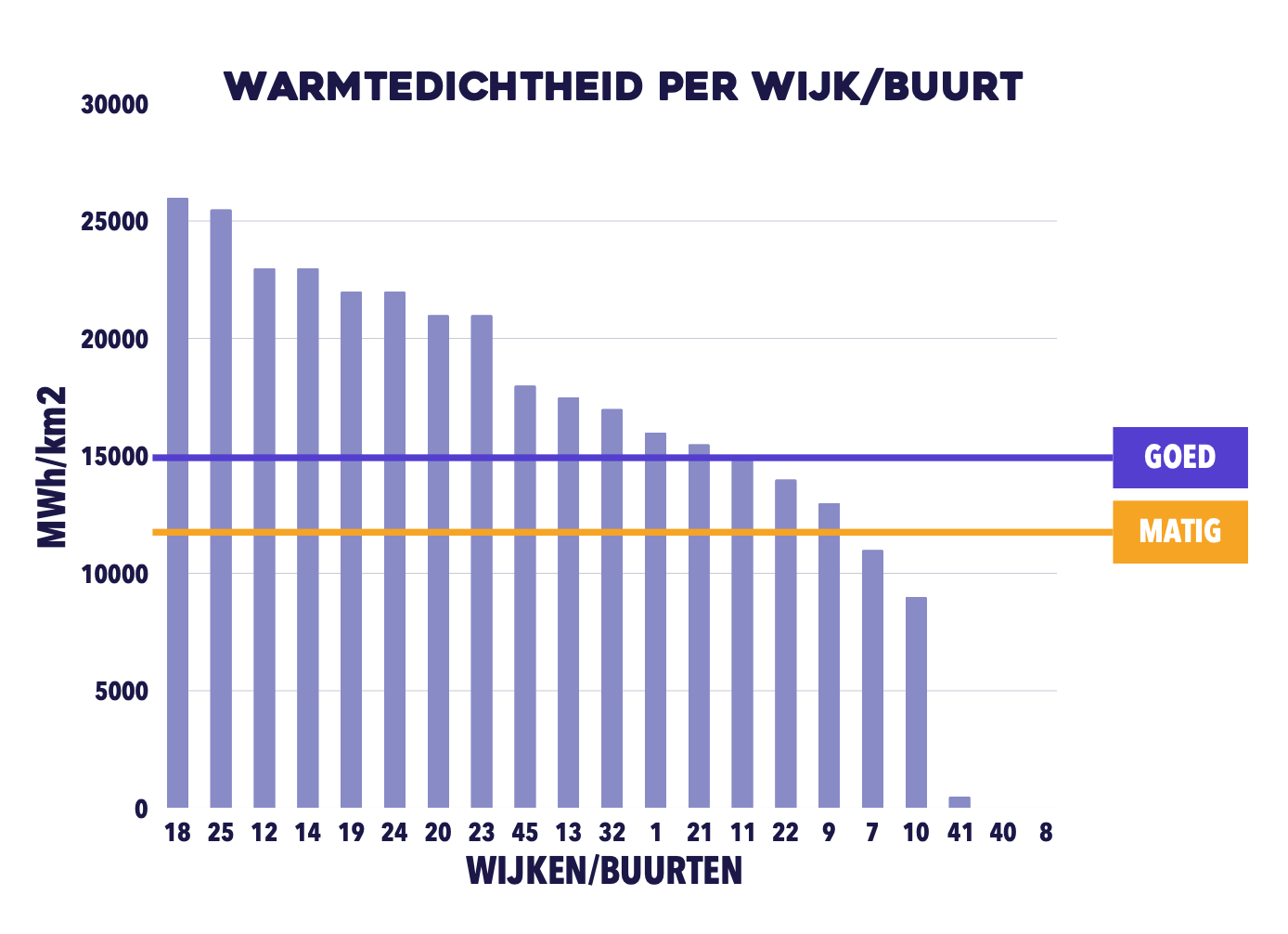

Figure 1: Heat demand for energy districts

In the figure above, energy district 18 has the highest energy density, followed by neighborhood 25. This means an efficient investment is possible. Because homes are closely situated, less infrastructure investment is required, and a high level of heat consumption is likely. In these energy districts, the chances of a profitable investment in district heating are the highest. By developing projects in this sequence and setting a single price level for the entire area, a surplus can be created. This surplus can then be used to make less viable projects feasible. Without this approach, less viable projects might never be realized. A commercial provider would likely choose only the most profitable projects and halt development afterwards.

If no Masterplan was in place, the bottom-up initiative might be project 9. (as seen in the figure). If development starts there and the project is made feasible with financial support, the required cost recovery contribution would be high. The risk is that decision-makers may then reject a second project due to the significant financial impact on the municipality’s financial resilience. Therefore, planning and vision are crucial to achieving municipal objectives.

Benefits of a Masterplan:

Provides insights into the phasing and feasibility of collective heating.

Prevents tunnel vision.

Makes phased development manageable both financially and organizationally.

Helps prioritize, starting with the most promising areas in the most suitable city, leading to a faster return on investment.

By starting in the most promising area, it helps to build the knowledge and expertise in practice needed to tackle more difficult projects in the future.

Enables well-founded decisions regarding potential investments in infrastructure over dimensioning of pipes (for scalability). Over dimensioning is a pre-investment that allows for efficient expansion of the heating network.

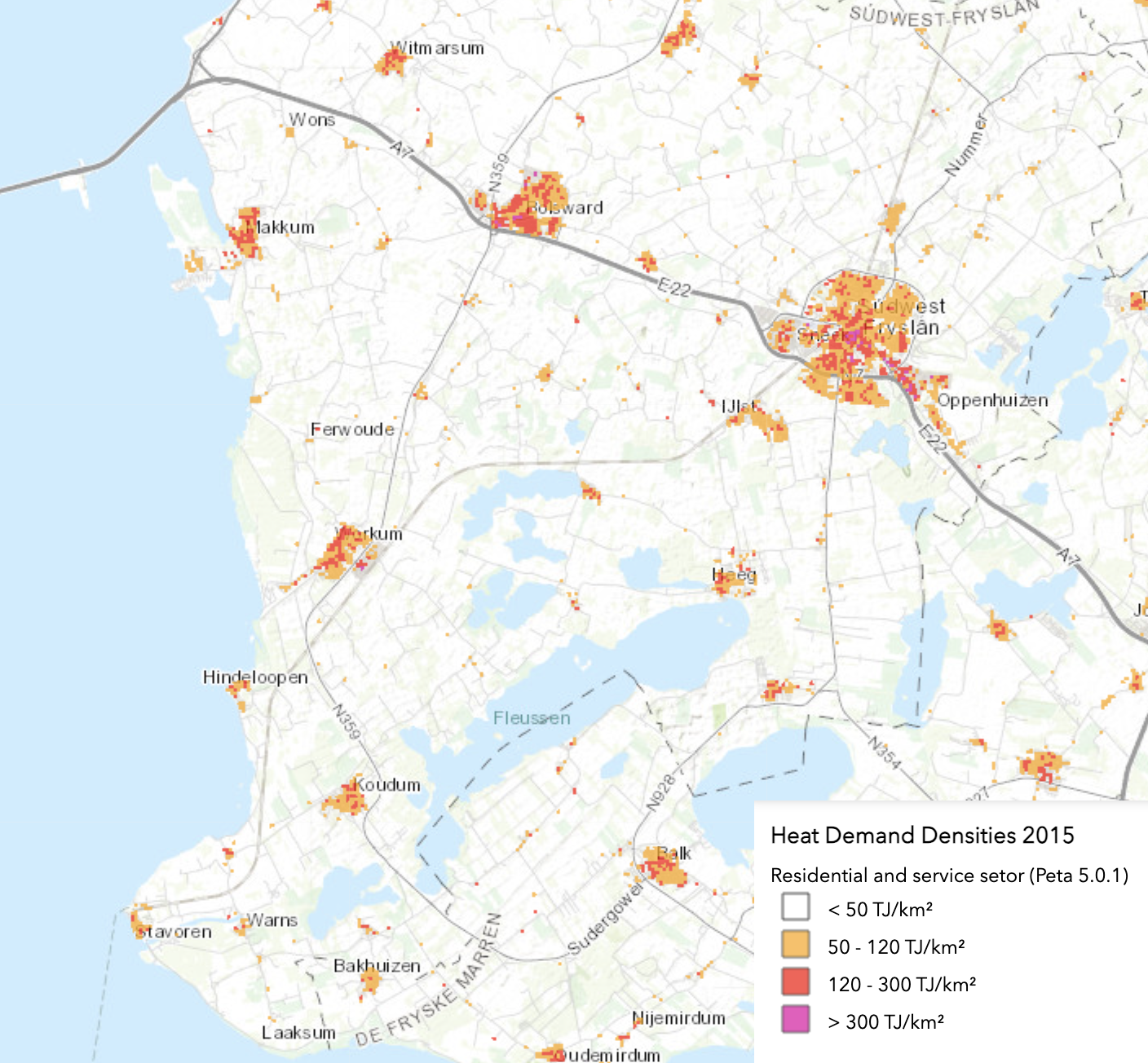

In Súdwest-Fryslân: The Masterplan consists of a municipal heat map and a source strategy, forming the basic structure for the entire municipality. The plan addresses heat demand density, available heat sources, and the potential for district heating networks. When we started this process, the only available resources pointed to only 5% of Súdwest-Fryslân having potential for district heating. Currently, we believe that up to 70% of our municipality has potential for district heating. We are currently developing our own heatmap in Fryslân in cooperation with Data Fryslân where we follow the Danish approach. This map will be made for the entirety of Fryslân so that other municipalities in the region can start taking these steps.

Figure 2: PETA 5.2: District heating potential from 50-120 TJ or higher of Southwest Fryslân.

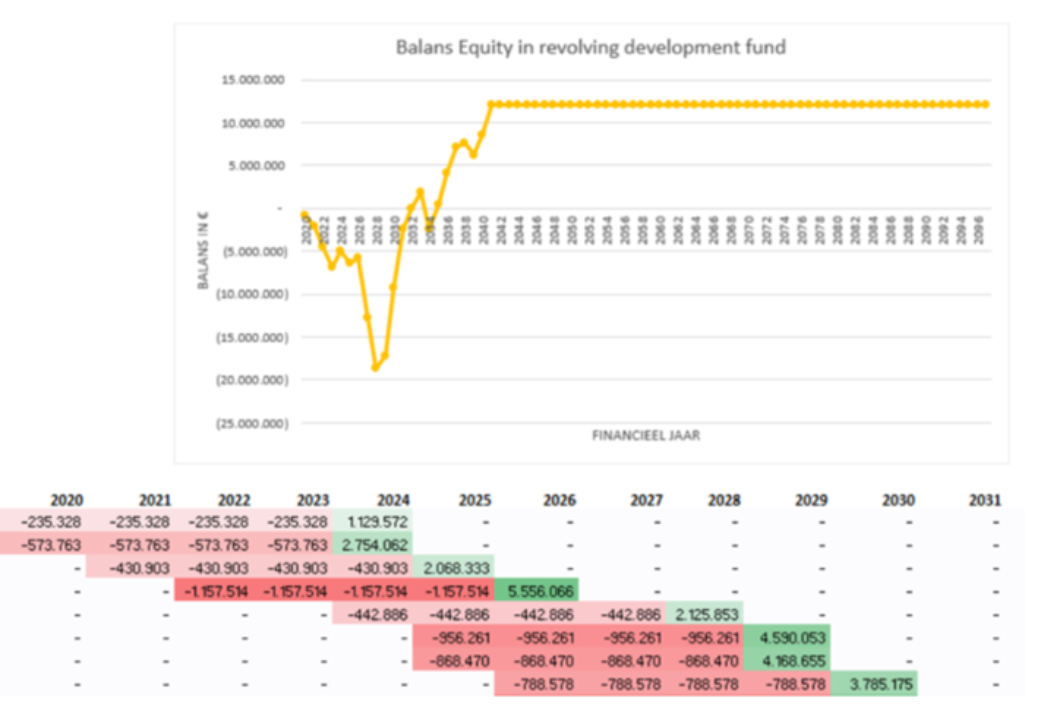

Step 3: Financial impact assessment

Once one or multiple potential projects are identified, a financial analysis of the plan’s impact on the municipality is possible. By creating a broad overview of all potential projects, including a general timeline for implementation, it can be assessed whether the objectives can be achieved and what impact this will have on municipal finances. Based on this impact, decisions can be made regarding the selection of projects to be carried out, and their financial implications.

Súdwest-Fryslân

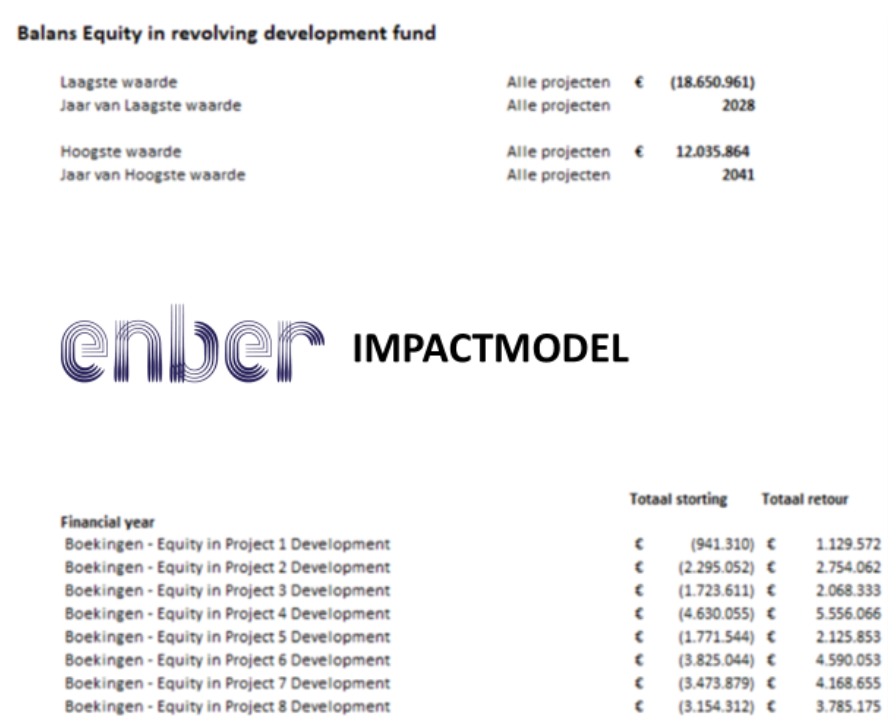

Through cooperation with Enber, the importance of mapping out the financial and organizational impact of these projects on our municipality came to the forefront. Initially, the feasibility of district heating in our region was still being debated, while there is now the possibility of launching several overlapping projects within the next five years. Now that we know that district heating is not only possible but preferred over alternative options, we are taking this step to outline which projects will be initiated, when, and in what order.

Step 4: Decision-making

Through the development of these three previous steps, the municipality now has a plan that includes:

A clear understanding of the role it wishes to take and how it intends to act, including its approach to stakeholders.

Insights from the Masterplan into which areas have the greatest potential for district heating.

An impact analysis that ranks projects and highlights their financial implications for the municipality.

As a result, the municipal council can make an informed decision on whether to adopt this approach and define its role, potentially leading to the establishment of a heating company or further exploration thereof.

Step 5: Engineering

Now that the council has approved the municipal broad plan, including the prioritization of projects, we can move forward with implementation. As previously mentioned, while it is essential to plan for the entire city, breaking the transition into manageable phases is crucial. This approach allows us to engineer a comprehensive city-wide solution while ensuring that the first phase generates revenue and surplus which can be reinvested into subsequent phases.

Pre-feasibility studies

These studies, like the master plan, provide an overview of the possibilities but go one level deeper into the situation in a specific area. These studies are conducted by Danish consultants who are experts in assessing the feasibility of district heating networks. Their insights are more detailed than what is currently available in the Netherlands. This will allow us to determine in which city and which neighbourhood we should start. This study provides:

Heat demand:

Preliminary network design:

Initial heat supply options:

Estimated heat price:

Súdwest-Fryslân

The municipality is passing through these steps. In Bolsward, there is currently a pre-feasibility study ongoing. In our preliminary reports, we find that there is a lot of potential for district heating and we are gaining insights in the Danish methodology. In our coming studies, we are learning from the Bolsward case to make the collaboration more efficient.

Detail phase: refining the Project

The detail phase refines the pre-feasibility study’s findings, focusing on the most promising area. Data is verified through discussions with residents, businesses, and contractors to assess heat demand, insulation levels, and interest in district heating.

A final inventory of potential heat sources is conducted, mapping waste heat availability and required infrastructure. Large heat consumers, such as hospitals and businesses, are engaged through letters of intent, alongside key partners like banks and energy providers.

With updated insights, the pre-feasibility study is refined, validating the business case. Coupling-opportunities are explored, aligning infrastructure plans with public works. A communication strategy informs residents and gathers feedback to ensure community support.

This phase delivers a validated business case and a phased rollout plan, providing a strong foundation for implementation.

Súdwest-Fryslân

Due to earlier pilot projects, we have a lot of information in some neighborhoods. In some pilots, intention agreements have already been made with the municipality, and data has also been shared. On this, we can build further.

Project proposal: securing approval and implementation

This last part of engineering finalizes the insights from the detail phase, developing a comprehensive business case for the first phases of the district heating network. Once the business case and coupling opportunities are finalized, an offer is presented to companies and residents involved in the initial phases. This step is crucial for confirming participation levels.

The final outcome is a well-supported plan for the entire area, including a rollout strategy and financial/technical decision-making framework. This plan, with advisory input from the municipal organization, is presented to the municipal board and council for phased approval.

Step 6: Construction

Once a project proposal is accepted by the municipal council, construction can begin. This is a milestone that the municipality of Súdwest-Fryslân hopes to achieve in the near future. While these steps are not a perfect pathway, we hope they can inspire other municipalities to begin the process—one that we have learned is far from linear. Developing a district heating network in a rural municipality requires a careful approach, balancing technical feasibility, affordability, sustainability, and social acceptance. By learning from previous projects and progressing step by step, municipalities can build a solid foundation for a sustainable heating system.